When you take a medication, you expect it to help - not hurt. But sometimes, drugs cause unexpected or unpleasant reactions. Not all side effects are the same. Some are common and predictable. Others are rare, dangerous, and hard to see coming. Understanding the difference between Type A and Type B adverse drug reactions (ADRs) can make the difference between a minor inconvenience and a life-threatening emergency.

What Are Type A Adverse Drug Reactions?

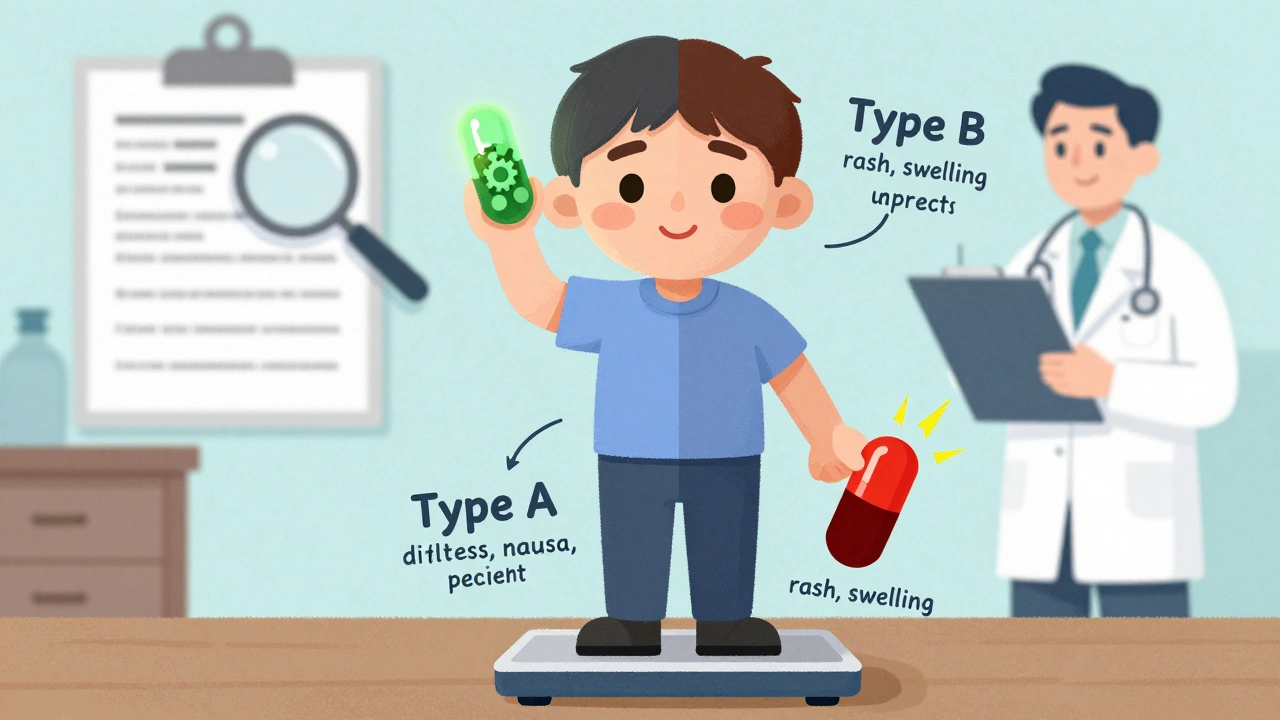

Type A reactions are the most common - making up 85 to 90% of all adverse drug reactions. They’re predictable, dose-dependent, and directly tied to how the drug works in your body. Think of them as an extension of the drug’s intended effect, just turned up too high.

For example, if you take an antihypertensive drug to lower your blood pressure, a Type A reaction might be your blood pressure dropping too far, leaving you dizzy or faint. Or if you take ibuprofen for pain, you might get stomach upset because the drug irritates the lining of your gut - something that happens in 15 to 30% of users. These aren’t rare. They’re normal side effects that show up in clinical trials and are listed in the drug’s package insert.

Other classic Type A reactions include:

- Low blood sugar from insulin or sulfonylureas in diabetes meds

- Bleeding risk from warfarin or aspirin when the dose is too high

- Sedation from benzodiazepines or antihistamines

- Constipation from opioids

The key thing about Type A reactions? They follow a clear pattern. The higher the dose, the worse the reaction. If you cut the dose, the problem usually goes away. That’s why doctors start with low doses and slowly increase them - to avoid these reactions before they start.

They’re also the easiest to prevent. Monitoring blood levels, adjusting doses, and watching for early signs like nausea, dizziness, or fatigue can stop most Type A reactions before they become serious. About 90% of hospitalizations from ADRs are due to Type A reactions - not because they’re rare, but because so many people take these drugs every day.

What Are Type B Adverse Drug Reactions?

Type B reactions are the opposite. They’re rare - only 5 to 10% of all ADRs - but they’re the ones that scare doctors the most. Why? Because they’re unpredictable. They have nothing to do with the drug’s normal action. They can happen at any dose, even a tiny one. And they can be deadly.

These are often called idiosyncratic or bizarre reactions. They’re not about how much you take - they’re about who you are. Your genes, your immune system, your liver enzymes - all of it plays a role. That’s why two people taking the same drug at the same dose can have totally different outcomes.

Examples of Type B reactions include:

- Stevens-Johnson syndrome from sulfonamides or allopurinol - a life-threatening skin reaction

- Anaphylaxis from penicillin - sudden swelling, trouble breathing, shock

- Malignant hyperthermia from anesthesia - dangerous spike in body temperature

- Drug-induced lupus from hydralazine or procainamide

These reactions don’t show up in clinical trials because they’re too rare. A drug might be tested on 10,000 people and never trigger one. Then, after millions of prescriptions, someone has a reaction. That’s why post-market surveillance is so important.

What makes Type B reactions even more dangerous is their mortality rate. While Type A reactions cause death in less than 5% of cases, Type B reactions kill in 25 to 30% of cases. That’s why a single Type B reaction can lead to a drug being pulled from the market - even if it works perfectly for 99.9% of people.

Why the Difference Matters in Real Life

Knowing whether a reaction is Type A or Type B changes everything - from how you treat it to whether you can ever take the drug again.

If you have a Type A reaction - say, nausea from metformin - your doctor might lower your dose, take you off it temporarily, or switch you to a different drug in the same class. You can usually try it again later, at a lower dose.

If you have a Type B reaction - like a severe rash from amoxicillin - you can never take that drug again. Not even a little bit. Your immune system now remembers it as a threat. Re-exposure could trigger an even worse reaction, like anaphylaxis.

And here’s the tricky part: some reactions sit in the middle. Take carbamazepine, used for seizures and nerve pain. It can cause low sodium levels. Is that Type A (dose-related) or Type B (idiosyncratic)? Studies show that at doses above 600 mg/day, sodium drops predictably - so it’s Type A. But some people get it at low doses with no clear pattern. That’s Type B. This overlap is why many clinicians now use a more detailed system.

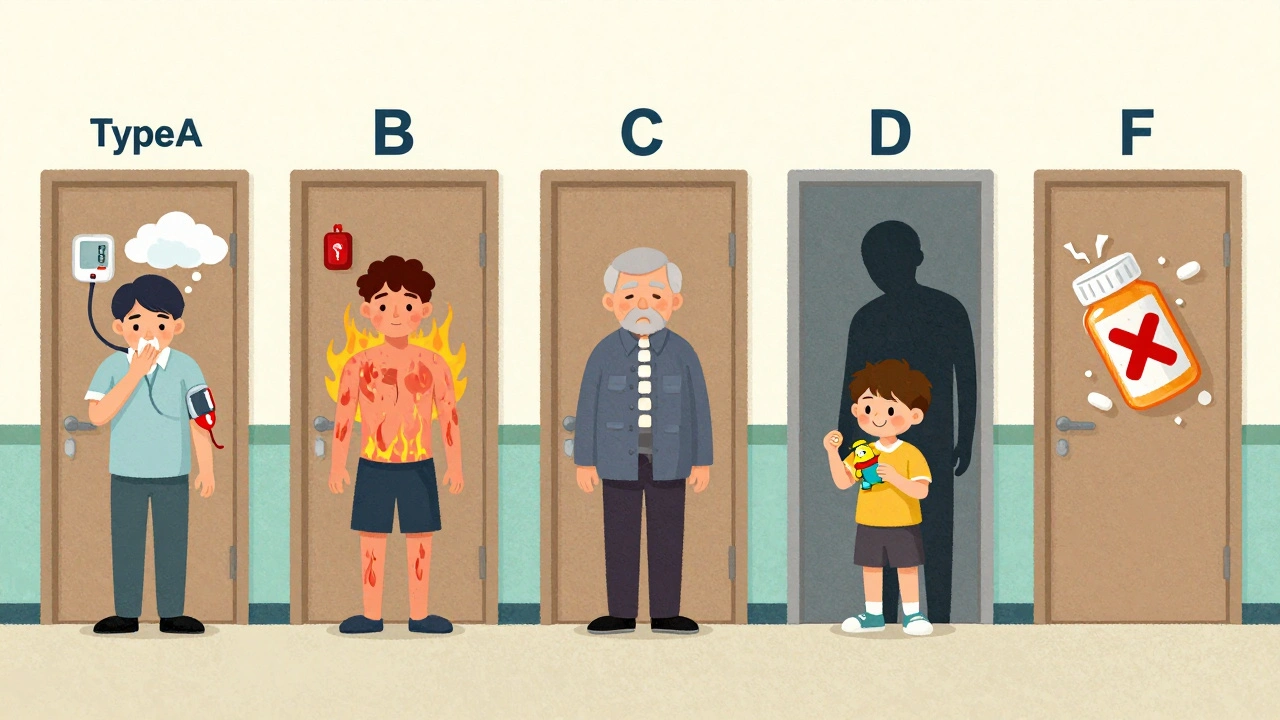

The Six-Type Classification System (A-F)

The basic Type A and Type B system works well for teaching and quick decisions. But in real-world practice, especially for serious reactions, it’s not enough. That’s why experts now use the expanded six-type system:

- Type A: Predictable, dose-related (as above)

- Type B: Unpredictable, idiosyncratic (as above)

- Type C: Chronic effects from long-term use - like adrenal suppression from steroids taken for more than three weeks, or osteoporosis from prolonged corticosteroid use

- Type D: Delayed reactions - like cancer in children born to mothers who took diethylstilbestrol in the 1950s, or tardive dyskinesia from long-term antipsychotics

- Type E: Withdrawal effects - like seizures from stopping benzodiazepines suddenly, or rebound hypertension after stopping clonidine

- Type F: Therapeutic failure - when a drug doesn’t work because of interactions, like birth control failing when taken with rifampin

This system gives doctors a much clearer picture. For example, if a patient on long-term prednisone develops cataracts, it’s not a random side effect - it’s a Type C reaction. If a patient on fluoxetine develops severe anxiety after stopping it, that’s Type E. These aren’t just side effects - they’re known patterns tied to duration or discontinuation.

According to the European Medicines Agency, 92% of pharmacovigilance centers in Europe now use the six-type system for serious ADR reporting. It’s becoming the global standard. The FDA and WHO are pushing for its adoption too, especially as AI tools start analyzing patterns in millions of patient records.

Immunological Classification: The Hidden Layer

Some Type B reactions are immune-mediated. That’s where the Types I-IV system comes in. It’s more detailed for allergic and immune reactions:

- Type I (IgE-mediated): Immediate - anaphylaxis to penicillin, peanut, or bee venom. Happens in minutes. Risk: 0.01-0.05% per course

- Type II (Cytotoxic): Antibodies attack your own cells - like drug-induced hemolytic anemia from methyldopa or penicillin

- Type III (Immune complex): Clumps of drug-antibody build up and cause inflammation - serum sickness from cefaclor, with fever, joint pain, and rash

- Type IV (Delayed, cell-mediated): T-cells react - maculopapular rashes from amoxicillin or vancomycin. Takes days to appear

This system doesn’t replace Type A/B - it complements it. If you get a rash from amoxicillin, you’d call it Type B (because it’s unpredictable), but also Type IV (because it’s T-cell driven). Knowing both helps you understand the risk and how to manage it.

What Clinicians Really Think

A 2022 survey of over 1,200 doctors found that 78% found the Type A/B system “moderately useful” - but only as a starting point. Most said they needed the six-type system to make real decisions.

Primary care doctors love it for teaching patients: “This nausea is common and will fade - that’s Type A.” But when a patient shows up with blistering skin or sudden liver failure, they switch to the six-type or immunological system fast.

One big problem? Ambiguity. About two-thirds of doctors say they’ve seen reactions that don’t clearly fit into one category. A reaction might start as dose-related but then become immune-driven. Or a genetic factor might turn what looked like Type A into Type B.

That’s why pharmacogenomics is changing everything. What used to be called “idiosyncratic” - like carbamazepine-induced SJS in people with the HLA-B*15:02 gene - is now predictable. We can test for it before prescribing. That’s turning Type B into Type A in disguise.

What You Should Do

If you’re taking a new medication:

- Ask your doctor: “What are the common side effects? Are they Type A?”

- Know the warning signs: Dizziness? Nausea? That’s likely Type A. Rash? Swelling? Trouble breathing? That’s Type B - get help immediately.

- Keep a log: Note when symptoms start, what dose you’re on, and if they get worse with higher doses.

- Report reactions: Use MedWatch or your country’s reporting system. Even if you’re not sure, report it. That data saves lives.

If you’ve had a reaction before:

- Always tell every new doctor - even if it happened years ago.

- Get an allergy bracelet if you’ve had a Type B reaction.

- Ask about genetic testing if you’re on high-risk drugs like carbamazepine, abacavir, or allopurinol.

The Future of Drug Safety

By 2027, experts predict that 60% of reactions once called “Type B” will have identifiable genetic markers. That means fewer surprises. More prevention. Fewer deaths.

AI tools are already scanning millions of patient records to spot patterns no human could see - like a drug linked to liver failure only in people with a specific enzyme variant.

But the core idea won’t change: drugs are powerful. They help - but they can hurt. Understanding the difference between predictable and unpredictable reactions isn’t just for doctors. It’s for anyone who takes medicine.

The goal isn’t to scare you. It’s to empower you. Know the signs. Ask questions. Report what you see. That’s how we make drugs safer for everyone.

Are Type A adverse drug reactions more common than Type B?

Yes, Type A reactions are far more common, accounting for 85 to 90% of all adverse drug reactions. They’re predictable, dose-related side effects like nausea from antibiotics or dizziness from blood pressure meds. Type B reactions are rare - only 5 to 10% - but they’re often more serious because they’re unpredictable and not tied to dose.

Can Type B reactions be prevented?

They can’t be prevented in most cases because they’re idiosyncratic - meaning they depend on your unique biology. But for some, genetic testing can help. For example, people with the HLA-B*15:02 gene should avoid carbamazepine because it greatly increases the risk of Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Avoiding known triggers and reporting past reactions to doctors also reduces risk.

Is a drug allergy always a Type B reaction?

Most drug allergies are Type B reactions because they’re immune-mediated and unpredictable. However, not all Type B reactions are allergies. Some are metabolic idiosyncrasies - like liver damage from acetaminophen in people with certain enzyme variants. True allergies (like anaphylaxis) fall under Type I-IV immunological classifications, which are a subset of Type B.

Why do some Type A reactions become dangerous?

Type A reactions become dangerous when doses are too high, when multiple drugs interact, or when a person has organ damage (like liver or kidney disease) that slows drug clearance. For example, taking too much acetaminophen causes liver failure - not because it’s toxic by nature, but because the liver can’t process it. That’s still Type A - just poorly managed.

Can a Type B reaction happen again if you take the drug?

Yes - and it’s often worse. Type B reactions involve your immune system or unique metabolism remembering the drug. Re-exposure can trigger a stronger, faster, and more dangerous reaction. That’s why doctors tell you to avoid the drug completely if you’ve had a serious Type B reaction like anaphylaxis or Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

What’s the difference between Type C and Type D reactions?

Type C reactions happen after long-term use - like osteoporosis from years of steroid use. Type D reactions are delayed in time, but not necessarily from long-term use - they appear years later, like cancer in children born to mothers who took DES during pregnancy. Type C is about duration; Type D is about timing of the effect, even after stopping the drug.

Fern Marder

December 2, 2025 AT 21:48Carolyn Woodard

December 4, 2025 AT 15:41Allan maniero

December 5, 2025 AT 23:28Anthony Breakspear

December 7, 2025 AT 09:31Zoe Bray

December 9, 2025 AT 09:00Girish Padia

December 10, 2025 AT 13:24Sandi Allen

December 12, 2025 AT 00:26Doug Hawk

December 13, 2025 AT 11:29John Morrow

December 13, 2025 AT 19:45Kristen Yates

December 14, 2025 AT 10:04Saurabh Tiwari

December 15, 2025 AT 07:53Michael Campbell

December 16, 2025 AT 16:14Victoria Graci

December 17, 2025 AT 10:04Saravanan Sathyanandha

December 18, 2025 AT 06:44