When a brand-name drug’s patent is about to expire, you’d expect a flood of cheap generics to hit the market. That’s the whole point of the Hatch-Waxman Act - to break monopolies and lower drug prices. But here’s what often happens instead: the original drug company launches its own authorized generic right as the first independent generic enters. And suddenly, the price drop isn’t as big as it should be.

What Exactly Is an Authorized Generic?

An authorized generic isn’t some knockoff. It’s the exact same pill, same factory, same formula as the brand-name drug - just packaged in a plain box with a generic label. The company that made the original drug sells it under a generic name, either through its own subsidiary or a licensed partner. No new approval needed. No new testing. Just a new label.

This isn’t a loophole. It’s legal. The FDA says so. The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 gave generic companies a 180-day window to be the only non-branded option on the market after a patent challenge. But it never said the brand company couldn’t jump in with its own version. And they did - fast.

How It Skews the Market

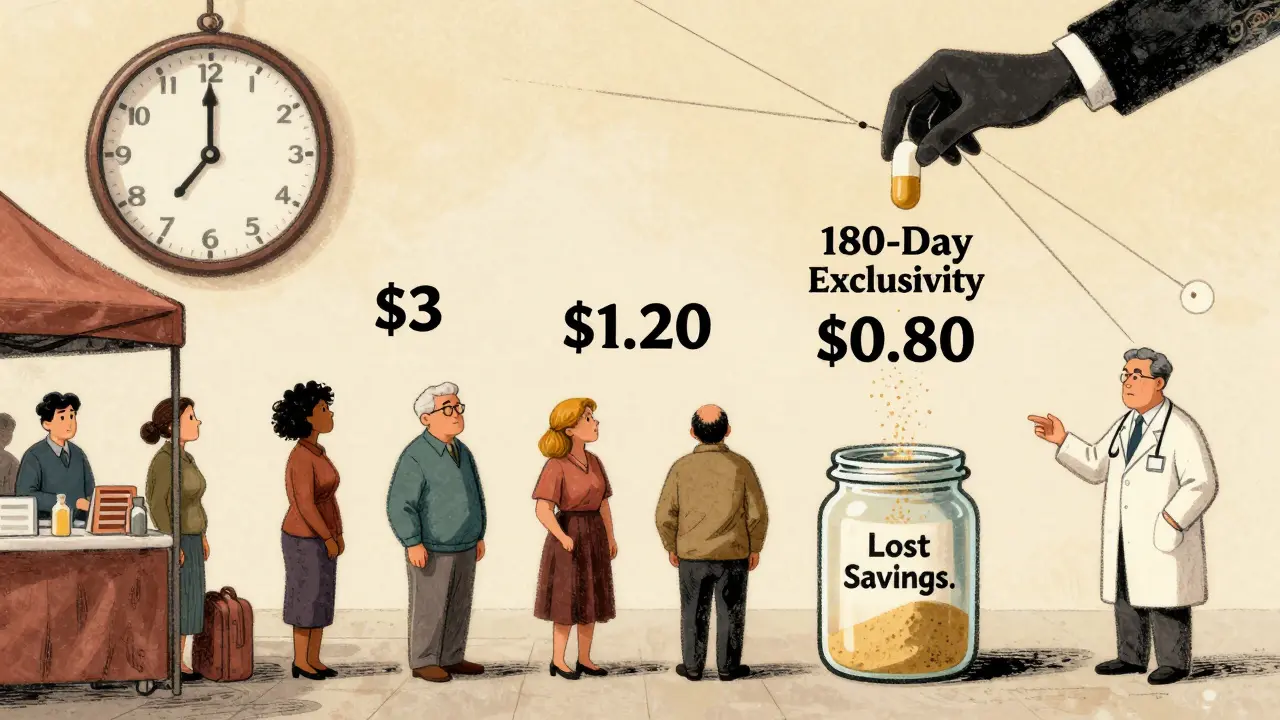

Picture this: a drug with $500 million in annual sales. The brand sells it for $3 a pill. The first generic company wins its patent challenge and prepares to launch at $0.80 a pill - a 73% drop. That’s what consumers and insurers expect.

Then, two weeks later, the brand company rolls out its authorized generic at $1.20 a pill. Same pill. Same packaging. Just cheaper than the brand. Now, instead of the generic taking 80-90% of the market, it gets stuck with 50-60%. The authorized generic grabs 25-35%. And the real price drop? It stalls.

The FTC studied this. In markets with authorized generics, the first generic’s revenue during its 180-day exclusivity period dropped 40-52%. Even three years later, those companies earned 53-62% less than they would have if no authorized generic had entered. That’s not competition. That’s sabotage from within.

The Settlement Trap

Here’s where it gets worse. Between 2004 and 2010, about 25% of patent litigation settlements involved an agreement: the brand company promised not to launch an authorized generic - in exchange for the generic company delaying its entry.

That’s called a "reverse payment." The brand pays the generic not to compete. And the authorized generic becomes the hidden tool. If the brand doesn’t launch its own version, the generic can dominate. But if the brand threatens to launch its own generic, the generic company backs down. The result? Market entry delayed by an average of 37.9 months. That’s over three years of higher prices for patients.

The FTC called this "the most egregious form of anti-competitive behavior." And they’re not alone. Former FTC Chairman Joseph Simons testified in 2019 that these deals "undermine the entire purpose of the Hatch-Waxman Act."

Who Benefits? Who Loses?

Branded drug companies say authorized generics help consumers by bringing down prices faster. They point to a 2024 Health Affairs study showing pharmacies paid 13-18% less for generics when an authorized version was available. But here’s the catch: the price drop isn’t as deep as it should be. The authorized generic sits between the brand and the true generic - a middle tier that keeps prices higher than they’d be otherwise.

Independent generic manufacturers say it’s a death blow. Teva reported a $275 million revenue loss in 2018 alone because of authorized generics. The Association for Accessible Medicines (formerly GPhA) argues it kills the incentive to challenge patents. Why spend millions on a lawsuit if the brand will just launch its own version and steal your market share?

Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), though? They mostly like it. A 2023 survey found 68% of PBM executives prefer formularies that include authorized generics. Why? Because they get more pricing options. More leverage. More room to negotiate. But that’s not the same as more competition.

The Legal Gray Zone

The Hatch-Waxman Act never mentioned authorized generics. That’s the problem. The law was written to encourage generic challenges. Instead, it became a playbook for delaying competition.

The Supreme Court stepped in with FTC v. Actavis (2013), ruling that reverse payment settlements could violate antitrust laws. But it didn’t touch authorized generics directly. So companies kept using them. The FTC responded by opening 17 investigations since 2020. In 2022, its director said they’d challenge "any arrangement that uses authorized generics to circumvent the competitive structure Congress established."

Is It Still Common?

It’s fading - but not gone. In 2010, 42% of markets with first-filer exclusivity saw an authorized generic launch. By 2022, that dropped to 28%. Why? Because regulators are watching. Because lawsuits are riskier. Because Congress keeps trying to ban them.

The Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act, reintroduced in 2023, would make it illegal to agree not to launch an authorized generic. If it passes, the practice could vanish overnight. But until then, companies still use it - especially on high-value drugs.

The Real Cost

The Congressional Budget Office estimated that banning authorized generics during the 180-day window could save Medicare $4.7 billion over ten years. That’s because more generics would enter, prices would drop faster, and fewer settlements would delay competition.

But here’s the quiet truth: for smaller drugs - ones with brand sales under $27 million a year - the threat of an authorized generic can stop a generic challenge before it even starts. Why spend $10 million on a lawsuit if you know the brand will just launch its own version and leave you with 10% of the market? That’s not innovation. That’s fear.

What’s Next?

Authorized generics aren’t going away because they’re illegal. They’re going away because they’re becoming too risky. The FTC is watching. Congress is drafting laws. Courts are growing skeptical. And the market? It’s changing.

Branded companies are learning to play by new rules. Some now wait until after the 180-day window to launch their authorized version. Others use third-party licensees to create distance. A few have stopped altogether.

But the system is still broken. The Hatch-Waxman Act was meant to speed up affordable drugs. Instead, it gave drug companies a legal way to protect their profits under the guise of competition. Until Congress closes this loophole, patients will keep paying more - not because generics are expensive, but because the system lets the original makers play both sides.

Are authorized generics the same as regular generics?

Yes, in every way that matters. Authorized generics are made in the same factory, with the same ingredients, dosage, and quality control as the brand-name drug. The only difference is the packaging and label. They’re not inferior - they’re identical. The difference is in how they enter the market: authorized generics are launched by the original drugmaker, while regular generics come from independent companies that challenge the patent.

Why do branded companies launch their own generics?

To protect their profits. When a patent expires, the brand expects to lose most of its sales. But if they launch their own authorized generic, they can keep a big chunk of the market - often 25-35% - while undercutting their own brand price. It’s a way to soften the financial blow of generic competition. In some cases, they even strike deals with independent generic companies to delay entry in exchange for not launching an authorized version.

Do authorized generics lower drug prices?

They lower prices a little - but not as much as true generic competition. An authorized generic usually costs 15-20% less than the brand, but 25-30% more than a regular generic. That means patients and insurers pay more than they should. Without authorized generics, the first generic company would typically capture 80-90% of the market and drive prices down much further.

Is it legal for a brand company to launch an authorized generic during the 180-day exclusivity period?

Yes, it’s legal. The FDA allows it, and courts have upheld the right of branded manufacturers to do so. The Hatch-Waxman Act doesn’t prohibit it. But while it’s legal, many regulators, including the FTC, argue it’s anti-competitive. The real controversy isn’t legality - it’s whether this practice undermines the intent of the law to encourage competition.

What’s being done to stop authorized generics from hurting competition?

The FTC has made it a priority. Since 2020, it has opened 17 investigations into agreements that delay generic entry using authorized generics. Congress has tried to ban them multiple times, most recently with the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act in 2023. Courts are also becoming more skeptical - especially after FTC v. Actavis. The trend is clear: the legal tolerance for this practice is shrinking.

James Lloyd

February 16, 2026 AT 05:39Authorized generics are a fascinating case study in regulatory unintended consequences. The Hatch-Waxman Act was designed to incentivize patent challenges, but it didn't anticipate that brand manufacturers would weaponize the very mechanism meant to dismantle their monopolies. What we're seeing isn't market competition-it's structural manipulation. The FDA's permissive stance on labeling and manufacturing equivalence ignores the economic reality: when the originator launches its own 'generic,' it doesn't just compete-it cannibalizes the incentive structure that makes generic entry viable in the first place.

There's a deeper issue here too. The 180-day exclusivity window was supposed to be a reward for risk-taking. Instead, it's become a bargaining chip in backroom deals. When a generic company knows the brand can drop an authorized version on day one, why spend $20 million on litigation? The math doesn't add up. And that’s not innovation-it’s deterrence dressed up as efficiency.

It’s also worth noting how PBMs benefit. They don’t care about competition; they care about margin arbitrage. More SKUs mean more leverage in rebates. But patients? They’re stuck paying $1.20 instead of $0.60 because the system rewards complexity over clarity. We’ve turned drug pricing into a labyrinth where the only winners are the ones who designed the maze.

Ultimately, this isn’t about legality-it’s about intent. Congress wrote a law to lower costs. The industry wrote a playbook to preserve them. And until we separate pharmaceutical manufacturing from market manipulation, we’re just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic of American healthcare.

Logan Hawker

February 17, 2026 AT 22:38Look, I get it-authorized generics are a 'legal' workaround, but let’s be real: this is corporate theater at its finest. You’ve got Big Pharma saying, 'We’re lowering prices!' while quietly siphoning off 30% of the market with a product that’s identical to the one they spent $2 billion developing. It’s not competition-it’s a Trojan horse wrapped in a white label.

And don’t even get me started on the reverse payment settlements. That’s not negotiation-it’s bribery with a law degree. The FTC’s been screaming into the void for years, but until Congress actually passes a ban (not just reintroduce a bill every two years), this will keep happening. We’re not talking about small-time drugs here-we’re talking about insulin, cancer meds, HIV cocktails. People are dying because of pricing games that should’ve been outlawed in 1995.

Also, why is no one talking about the fact that these 'authorized' generics are often produced in the same facilities as the brand? That’s not 'competition'-that’s the same factory, same line, same workers, same QA protocols-just a different box. It’s like McDonald’s launching 'McDonald’s Burger Lite' right when a competitor opens a burger joint down the street. You’re not lowering prices-you’re just making the customer choose between two versions of the same thing.

And yet, somehow, this is still considered 'market efficiency.' I’m not a doctor. I’m not a lawyer. I’m just someone who pays for my meds. And I’m tired of being played.

Sam Pearlman

February 19, 2026 AT 04:54Carrie Schluckbier

February 19, 2026 AT 13:43Let’s not pretend this is about competition. This is a coordinated, multi-billion-dollar scheme to delay generic entry. The FTC’s investigations? A distraction. The real players? The same lobbyists who wrote the Hatch-Waxman Act in the first place. They’re not just using authorized generics-they’re weaponizing them. And the FDA? They’re complicit. How many times have you heard 'It’s legal!'? That’s not a defense-it’s a confession.

And don’t forget: every time a generic company backs down because of a threat, it’s not just about money. It’s about fear. Fear of lawsuits. Fear of losing their investors. Fear that the next time they challenge a patent, the brand will bury them under a flood of authorized versions. This isn’t market dynamics-it’s psychological warfare.

There’s a reason Congress keeps trying to ban this. Because they know. And if you think the pharmaceutical industry doesn’t have a dossier on every single legislator who’s ever voted on this? You’re delusional.

Steph Carr

February 20, 2026 AT 01:57So we’ve got a system where the law rewards litigation, but the market rewards surrender. The brand company doesn’t need to win in court-they just need to make the challenger think twice. It’s not capitalism. It’s performance art with a balance sheet.

And the irony? The people who scream loudest about 'free markets' are the same ones who engineered this monopoly-with-a-makeup-job. You want competition? Fine. But let’s not pretend that a company launching its own version of a product it spent decades patenting is 'market-driven.' That’s not competition. That’s control with a different label.

Meanwhile, patients are stuck choosing between 'Brand Name' and 'Brand Name Lite'-both made in the same factory, both owned by the same corporation, both priced to maximize profit, not access. We’re not fixing healthcare. We’re just repackaging it.

And let’s not forget-the 180-day window was supposed to be a prize. Now it’s a hostage situation. The generic company wins the case… and gets a middle finger and a 25% market share. Bravo. What a system.

Liam Earney

February 21, 2026 AT 22:04It’s profoundly disturbing, isn’t it? The entire architecture of pharmaceutical regulation-designed with such noble intentions, grounded in the belief that innovation should be rewarded, but access should be universal-has been subtly, insidiously, and systematically subverted by a set of legalistic loopholes that, while technically compliant, violate every principle of fairness and public interest.

When a company manufactures a product, owns the intellectual property, controls the supply chain, and then, at the precise moment of market opening, deploys a clone of its own product under a different label-this is not market dynamics; this is the institutionalization of predatory behavior under the banner of legality. And the fact that regulators, courts, and even some economists have accepted this as 'acceptable competition' speaks volumes about how far we’ve drifted from the ethos of public health.

It’s not merely that authorized generics suppress price drops; it’s that they erode trust. Trust in the system. Trust in the FDA. Trust in the notion that the law is meant to serve the people, not the shareholders. And when patients begin to perceive that their medications are being manipulated by corporate calculus rather than scientific necessity, the entire foundation of healthcare legitimacy begins to crack.

There is a quiet, creeping cynicism in this country-not loud, not protest-y-but deep, and it is rooted in the realization that we are being sold solutions that are designed to preserve profit, not promote health. And that, more than anything, is the true cost of authorized generics.

Adam Short

February 23, 2026 AT 06:04Let’s be brutally honest: the U.S. is the only country in the developed world where this nonsense is allowed. In the UK, EU, Canada, Australia-when a patent expires, the brand gets kicked off the shelf. Full stop. No authorized generics. No 'market manipulation.' Just competition. And guess what? Prices plummet. Patients win.

Here, we’ve turned pharmaceutical policy into a poker game where the house always wins. The FDA says it’s legal? Fine. But legality doesn’t equal morality. And let’s not pretend Congress doesn’t know this. The pharmaceutical lobby spends more on lobbying than any other industry. That’s not democracy. That’s a pay-to-play oligarchy.

And now we’re supposed to applaud when a company 'lowers prices' by launching its own version? That’s like a thief saying, 'I didn’t steal your wallet-I just took half the cash and gave it back to you with a receipt.'

It’s time we stop pretending this is about healthcare. It’s about profit. And until we treat drugs like a public good-not a profit center-we’re all just paying extra for the privilege of being exploited.

guy greenfeld

February 24, 2026 AT 23:54There’s a metaphysical dimension to this that no one wants to talk about. We’ve turned medicine into a transactional abstraction-a commodity stripped of its ethical weight. The authorized generic isn’t just a product; it’s a symbol of how deeply we’ve lost the narrative of healing. The drug is no longer a cure. It’s a financial instrument. The patent isn’t an incentive-it’s a weapon. The generic isn’t access-it’s a bargaining chip.

When a company launches its own 'generic,' it’s not lowering prices. It’s performing the illusion of benevolence while maintaining control. It’s capitalism’s final evolution: the monopoly that pretends to be competitive. And we, the consumers, are the willing participants in this theater, nodding along as if the difference between a blue pill and a white pill is anything more than a branding exercise.

Perhaps the real question isn’t how to ban authorized generics-but whether we still believe in the idea that health should be a right, not a market outcome. Because if we don’t, then this isn’t a loophole in the law. It’s the natural conclusion of a system that values profit over personhood.

Digital Raju Yadav

February 26, 2026 AT 14:36USA is a joke. You have the best pharmaceutical R&D in the world, but you let corporations turn life-saving drugs into a monopoly game. India makes generics for the whole world-cheap, safe, effective. But here? You have companies that patent a pill, then launch their own fake generic to keep prices high. This is not innovation. This is theft.

And don’t tell me about 'legal.' Legal doesn’t mean right. China, Russia, Brazil-they all have stricter rules. Why? Because they don’t let corporations control healthcare. You let Wall Street write your drug laws. No wonder your insulin costs 10x more than in Bangladesh.

Stop pretending this is about competition. This is about greed. And until the U.S. wakes up and stops treating medicine like a stock market, people will keep dying because of a loophole written by lobbyists.

Brenda K. Wolfgram Moore

February 28, 2026 AT 07:13What’s really remarkable is how this whole system still functions at all. The fact that authorized generics haven’t completely collapsed under their own hypocrisy is a testament to how much inertia there is in the system. But here’s the thing: every time a generic company walks away from a patent challenge because of this, we lose a little more of what makes innovation meaningful.

It’s not just about price. It’s about trust. When the people who are supposed to be the challengers-the ones risking everything to break monopolies-start backing down because the system is rigged, we’re not just losing competition. We’re losing the next generation of innovators who might’ve dared to try.

And yes, PBMs like it. Sure. More options. More rebates. But that’s not healthcare. That’s accounting. Real progress would be a system where the lowest price wins-not the one with the most legal loopholes.

Maybe the answer isn’t just banning authorized generics. Maybe it’s rebuilding the entire incentive structure so that competition isn’t something you have to fight against-it’s something you’re rewarded for.