When you pick up a prescription for metformin, lisinopril, or atorvastatin, there’s a 90% chance it’s a generic drug. These pills look different from the brand-name versions you see in TV ads, cost a fraction of the price, and yet work just the same. But how exactly are they made? It’s not just copying a pill. It’s a precise, highly regulated science that takes years, millions of dollars, and strict controls to get right.

What Makes a Drug "Generic"?

A generic drug isn’t a copycat. It’s a therapeutic twin. By law, it must contain the same active ingredient, in the same strength, same dosage form (tablet, capsule, injection), and same route of administration (oral, topical, etc.) as the original brand-name drug. The FDA requires it to deliver the same amount of medicine into your bloodstream at the same rate. That’s called bioequivalence. If a generic drug’s absorption rate falls outside 80%-125% of the brand-name version’s, it’s rejected.What’s allowed to be different? The color, shape, flavor, or inactive ingredients-like fillers, binders, or coatings. These don’t affect how the drug works, but they help manufacturers avoid trademark issues. You can’t make a generic version of a blue oval pill if the brand’s pill is blue and oval. So generics often come in different shapes or colors, even if they contain the exact same medicine.

The Legal Shortcut: The ANDA Process

Branded drugs take 10-15 years and over $2 billion to develop. They go through years of lab testing, animal trials, and massive human studies to prove safety and effectiveness. Generic drug makers don’t need to repeat all that. Instead, they use the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway, created by the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act.The ANDA is "abbreviated" because it leans on the original drug’s data. The generic company doesn’t prove the medicine works-they prove their version behaves the same way in the body. This cuts development time to 3-4 years and costs $5-10 million per drug.

The ANDA process has five key steps:

- Submit the application with detailed chemistry, manufacturing, and control data

- Prove bioequivalence through human studies (usually 24-36 healthy volunteers)

- Pass an FDA inspection of the manufacturing facility

- Get labeling approved-must match the brand’s in content, even if the layout differs

- Enter the market and stay under FDA monitoring

There’s also a legal chess game around patents. Generic companies can file a "Paragraph IV" certification, claiming the brand’s patent is invalid or not infringed. This often triggers lawsuits that can delay the generic’s launch by up to 30 months.

Step-by-Step: How a Generic Pill Is Made

Manufacturing a generic drug isn’t just mixing powder and pressing it. It’s a seven-stage, tightly controlled process that starts with reverse-engineering the original product.1. Reverse Engineering the Reference Drug

Before making a single tablet, manufacturers get the brand-name drug-called the Reference Listed Drug (RLD)-and break it down. They use advanced lab tools to identify every ingredient: the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), the fillers, the coatings, even the particle size of each component. This isn’t guesswork. It’s analytical chemistry at its most precise.2. Formulation Design Using Quality by Design (QbD)

Modern generic manufacturing follows the Quality by Design framework, set by the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH). This means manufacturers don’t just aim to match the final product-they design the process to consistently hit the target.They define:

- Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs): What matters for safety and effectiveness-like how fast the drug dissolves

- Critical Material Attributes (CMAs): Properties of raw materials that affect quality-like how fine the lactose powder is

- Critical Process Parameters (CPPs): What settings in the machine can change the outcome-like pressure during compression or drying time

Change one of these, and the whole batch might fail. That’s why a slight difference in lactose particle size from a supplier can throw off tablet hardness and dissolution-something a pharma engineer on Reddit said is "the biggest headache" in production.

3. Mixing and Granulation

The API is blended with excipients-fillers like microcrystalline cellulose, binders like povidone, and disintegrants like croscarmellose sodium. This mixture is turned into granules, either by wet granulation (adding liquid) or dry granulation (using rollers). Granulation ensures even distribution of the active ingredient. If the API isn’t evenly mixed, some pills get too much medicine, others too little.4. Drying

If wet granulation was used, the granules are dried in ovens or fluid bed dryers. Moisture content must be tightly controlled-too much, and the tablets crumble or degrade. Too little, and they become too hard to dissolve. The ideal range is usually 1-3% water.5. Compression and Encapsulation

Dry granules are pressed into tablets using high-speed tablet presses. Each machine can make over 1 million tablets per hour. The pressure must be exact-too little, and tablets break. Too much, and they won’t dissolve properly.For capsules, the granules are filled into gelatin or vegetarian capsules using automated fillers. Each capsule is weighed and checked for fill weight consistency.

6. Coating

Most tablets get a coating. Why?- To mask bad taste

- To protect the drug from stomach acid (enteric coating)

- To control release (extended-release coatings)

- To make pills easier to swallow

Coating is sprayed on in large tumbling drums. The thickness and composition must match the brand. Even a 5% difference can change how quickly the drug releases in the body.

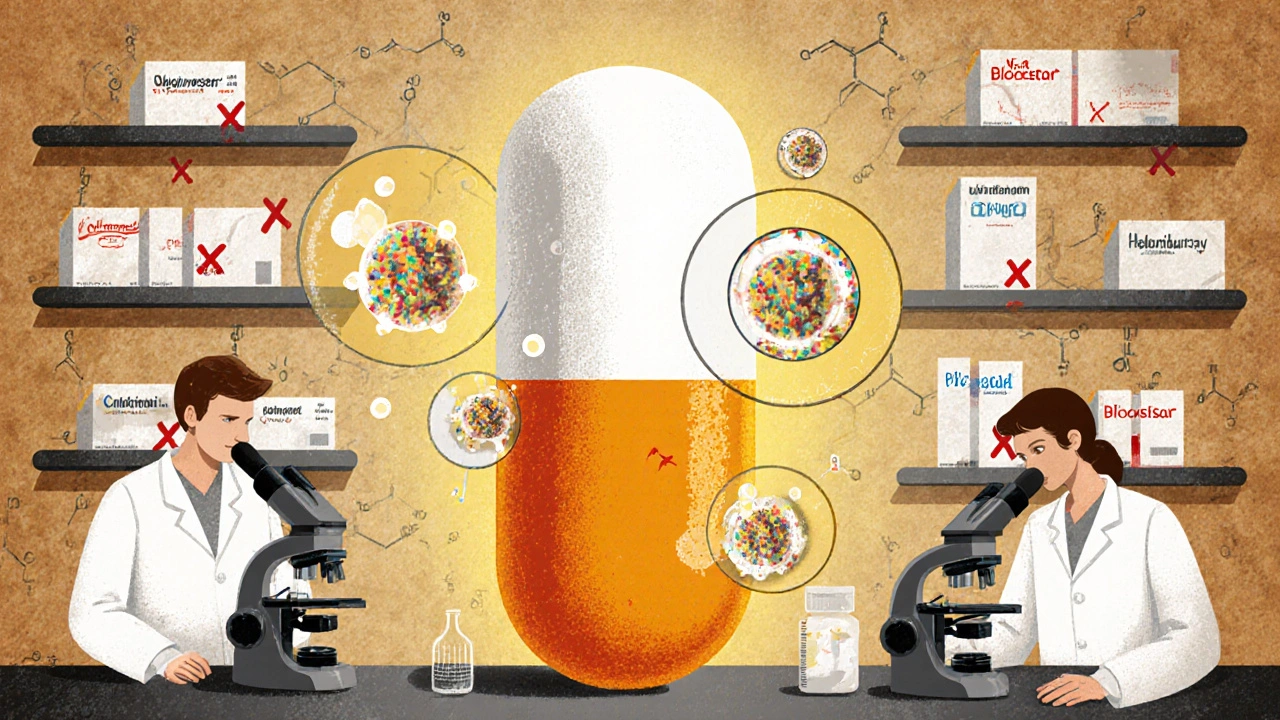

7. Quality Control and Testing

This isn’t one step-it’s woven into every stage. Every batch is tested for:- Identity: Is the right drug in there?

- Strength: Does it have the correct amount of API?

- Purity: Are there harmful impurities?

- Dissolution: Does it release the drug at the right rate?

- Uniformity: Are all tablets the same weight and content?

Tablet weight variation? Must be within ±5% for pills under 130mg, or ±7.5% for pills between 130-324mg. Dissolution tests must show the generic releases the drug within the same time window as the brand.

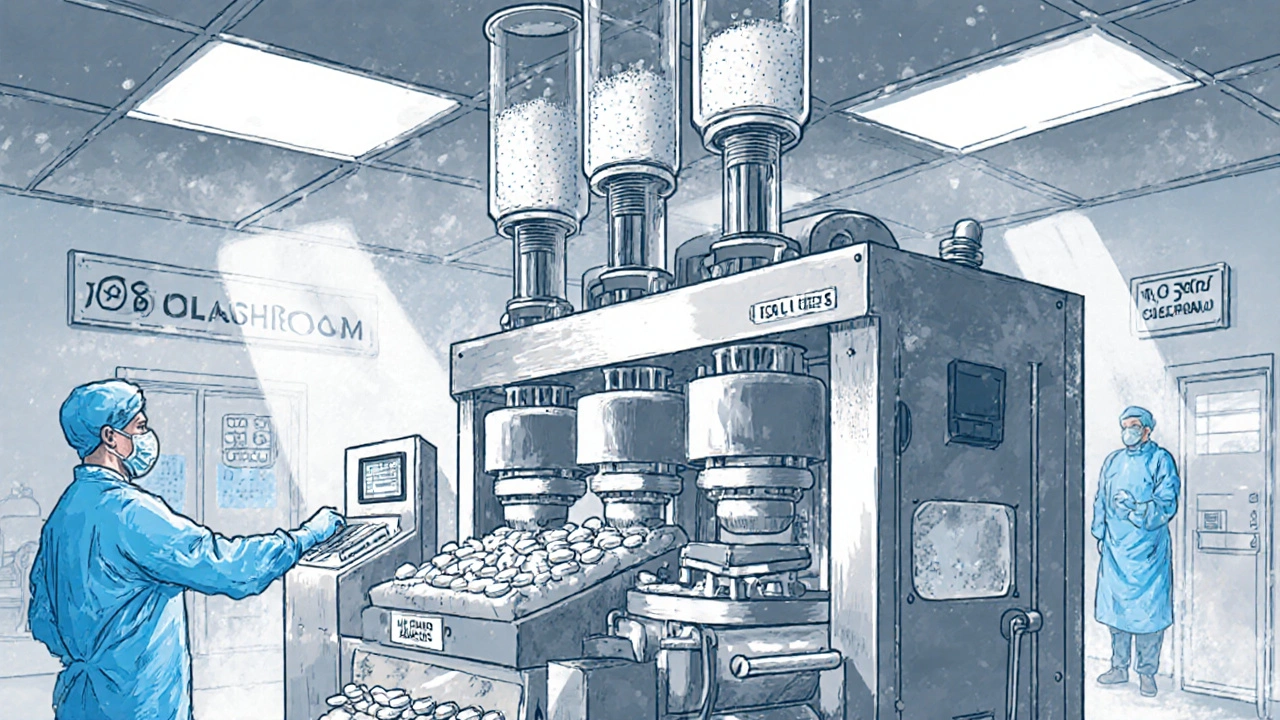

Manufacturing Standards: CGMP and Cleanrooms

All generic drug factories must follow Current Good Manufacturing Practices (CGMP) set by the FDA. These aren’t suggestions-they’re legal requirements.Facilities are divided into cleanrooms:

- ISO Class 5: For sterile products like injections

- ISO Class 7-8: For tablet and capsule production

Temperature is kept at 20-25°C. Humidity is controlled at 45-65% RH. Air filters remove particles. Workers wear gowns, masks, and gloves. Every step is documented. If a machine goes out of spec, the team has 24 hours to investigate why.

The FDA inspects these plants regularly. In 2023, the most common violations were:

- 37%: Inadequate investigation of out-of-spec results

- 29%: Insufficient process validation

- 24%: Poor quality unit oversight

One major recall in 2021 involved Teva’s Puerto Rico plant, where CGMP failures led to 14 generic drugs being pulled from shelves. That’s why pharmacists trust generics-but only if they know the manufacturer has a clean record.

Complex Generics: The New Frontier

Not all generics are created equal. Simple pills like amoxicillin have dozens of manufacturers. But complex products-like inhalers, topical creams, eye drops, or extended-release tablets-are much harder to copy.Why? Because you can’t just test blood levels and call it good. For a generic inhaler, you need to match the spray pattern, particle size, and how deep it goes into the lungs. For a topical cream, you need to match how it spreads and absorbs through the skin.

A 2022 case study showed a company spent 7 years and $47 million to match a generic version of Clobetasol Propionate cream. Even then, the FDA required special testing because traditional bioequivalence didn’t predict real-world performance.

That’s why complex generics now make up 35% of all pending ANDAs-up from just 12% in 2015. And they’re more profitable. While simple generics lose 80% of their price within two years, complex ones drop only 20-30% over five years because fewer companies can make them.

Why It Matters: Savings, Access, and Trust

Generic drugs saved U.S. healthcare $1.7 trillion over the last decade. In 2023, 90% of all prescriptions filled were generics. That’s not just a number-it’s a mother choosing between insulin and groceries. A veteran getting his blood pressure meds without rationing. A child getting antibiotics because the brand was unaffordable.But trust is fragile. When a generic fails, it’s not just a business loss-it’s a health risk. That’s why the FDA’s inspection regime, though imperfect, is vital. Leading manufacturers like Dr. Reddy’s require 160 hours of initial GMP training and 40 hours yearly for every employee. Documentation for a single ANDA can run 5,000-10,000 pages.

And while critics point to occasional quality issues, the data is clear: 89% of pharmacists report no meaningful difference in patient outcomes between generics and brands. The science, the regulations, and the real-world evidence all point to the same conclusion: generic drugs work.

What’s Next: AI, Digital Twins, and Continuous Manufacturing

The future of generic manufacturing is faster, smarter, and more precise.Continuous manufacturing-where ingredients flow through a system in real time instead of in batches-is now approved for 17 generic drug plants. It cuts production from weeks to hours and reduces defects. One company using it for a cystic fibrosis drug saw batch acceptance rates jump from 95% to 99.98%.

AI is being used to spot defects in pills during visual inspection. Pfizer’s pilot program cut errors by 40%. "Digital twins"-virtual models of the manufacturing line-let engineers simulate problems before they happen.

And the FDA is updating its rules. GDUFA IV, in effect since October 2022, now requires 90% of ANDAs to be reviewed in 10 months-down from 17. The goal? More generics, faster.

With $75 billion in branded drugs set to lose patent protection by 2027, the demand for generics will only grow. The system isn’t perfect. But for millions of people who rely on affordable medicine, it’s the only thing standing between them and unaffordable care.

Are generic drugs as safe as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generic drugs to meet the same strict standards for safety, strength, purity, and quality as brand-name drugs. They must prove bioequivalence-meaning they deliver the same amount of medicine into your bloodstream at the same rate. Millions of people use generics every day without issue. The FDA inspects manufacturing plants regularly and pulls products off shelves if they don’t meet standards.

Why do generic pills look different from brand-name ones?

U.S. trademark law prevents generic drugs from looking exactly like brand-name versions. That’s why generics may have different colors, shapes, or sizes. But the active ingredient, dose, and how it works in your body are identical. The differences are only in inactive ingredients like dyes or coatings, which don’t affect the drug’s performance.

Do generic drugs take longer to work?

No. To be approved, a generic must prove it works at the same rate as the brand-name drug. This is tested in bioequivalence studies where volunteers take both versions and their blood levels are measured. If the generic’s absorption rate doesn’t fall within 80%-125% of the brand’s, it won’t be approved. So timing is identical.

Why are some generic drugs more expensive than others?

Price differences come down to competition and complexity. Simple generics like ibuprofen have dozens of manufacturers, so prices drop to pennies. Complex generics-like inhalers or extended-release pills-have fewer makers, so prices stay higher. Also, if a drug is hard to make (like a topical cream), the cost of development and testing pushes the price up. Supply chain issues, like API shortages from overseas, can also cause price spikes.

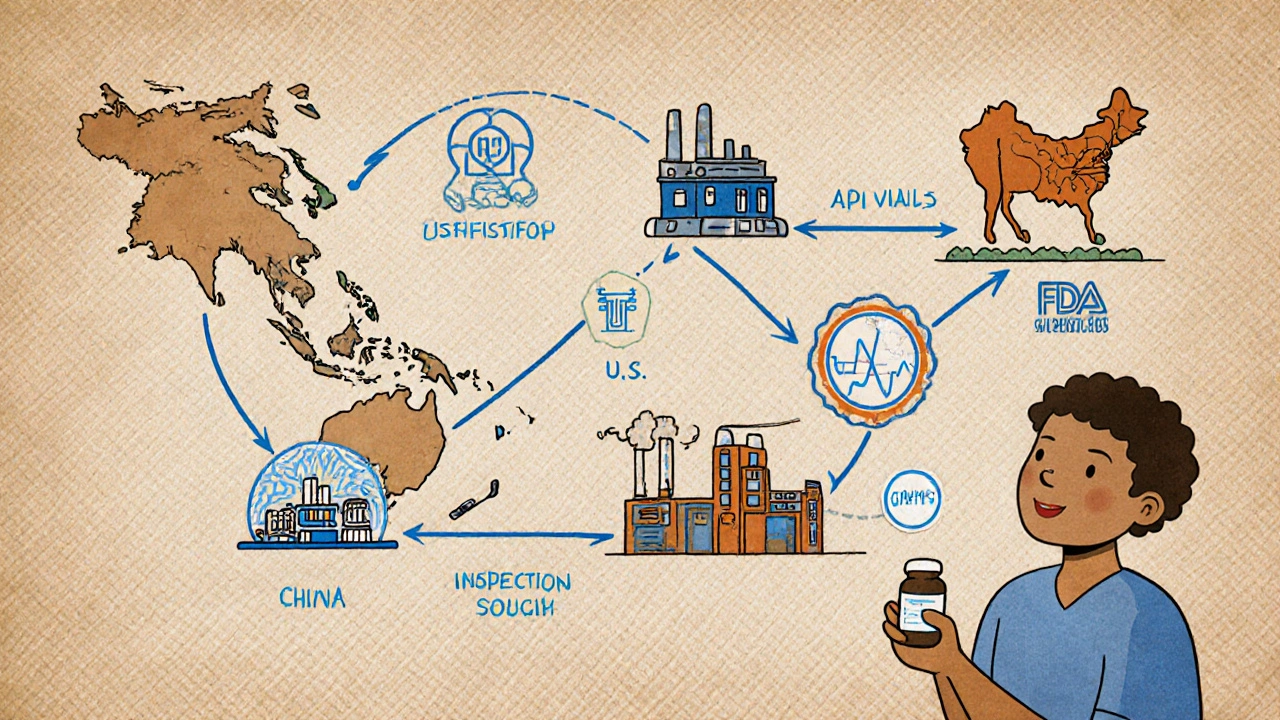

Where are generic drugs made?

Most active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) for generic drugs come from China and India-78% of U.S. supply, according to 2023 FDA data. Final manufacturing happens in the U.S., Europe, and other countries with FDA-approved facilities. The FDA inspects all plants, whether they’re in the U.S., India, or China. A drug made in India is held to the same standard as one made in New Jersey.

Can I trust a generic drug if it’s made overseas?

Yes. The FDA inspects foreign manufacturing facilities just like U.S. ones. In fact, more than half of all FDA-approved drug facilities are overseas. A drug made in India or China is subject to the same CGMP rules as one made in the U.S. If a plant fails inspection, the FDA blocks imports. There’s no difference in safety standards based on location.

What’s the difference between generic and biosimilar drugs?

Generics are copies of small-molecule drugs-like pills you swallow. Biosimilars are copies of complex biologic drugs-like injectables made from living cells (e.g., Humira or Enbrel). Biosimilars are harder to replicate because their molecules are much larger and more complex. They require more testing than generics and are not considered interchangeable by default. The FDA has separate rules for biosimilars under its Biosimilars Action Plan.

Mira Adam

November 28, 2025 AT 09:05So let me get this straight-we’re paying billions for brand-name drugs that are literally just repackaged generics with a fancy logo and a TV ad budget? The system isn’t broken, it’s designed to bleed you dry while pretending it’s saving lives. This isn’t science-it’s corporate theater with FDA stamps.

Miriam Lohrum

November 30, 2025 AT 05:37It’s fascinating how we’ve turned medicine into a puzzle of regulatory loopholes and patent chess. The real miracle isn’t the drug-it’s that the system still works at all. People forget that behind every pill is a team of chemists, engineers, and inspectors working in silence so you don’t have to choose between rent and refills.

reshmi mahi

December 2, 2025 AT 02:27India makes 78% of the world’s generics and you guys still act like they’re sketchy? 😂 We make pills that save your grandmas and you call us "outsourcing" like it’s a crime. At least we don’t charge $1000 for a pill that’s just aspirin with a brand name. 🇮🇳💊

laura lauraa

December 2, 2025 AT 11:34Let me just say-this entire system is a grotesque parody of medical ethics. The FDA? A toothless watchdog. The ANDA process? A loophole masquerading as innovation. And yet, here we are, trusting our lives to pills made in factories where the air is filtered but the accountability isn’t. I’m not saying it’s all bad-I’m saying it’s terrifyingly fragile.

Gayle Jenkins

December 4, 2025 AT 11:32Y’all need to stop treating generics like they’re second-class medicine. They’re not. The science is solid, the testing is brutal, and the people who make them? They’re engineers who care more about your health than some CEO’s quarterly report. If you’ve ever taken a pill that kept you alive and didn’t bankrupt you-you’re already living proof that this system works.

Kaleigh Scroger

December 5, 2025 AT 01:55What people don’t realize is that the real bottleneck isn’t making the pill-it’s proving it dissolves right. One micron of particle size difference and the whole batch gets tossed. I’ve seen labs spend six months just tweaking a coating because the dissolution curve was off by 0.7 minutes. That’s not laziness-that’s obsessive precision

Elizabeth Choi

December 5, 2025 AT 19:3289% of pharmacists report no difference? That’s a cherry-picked stat. What about the 11% where patients had seizures, rashes, or dropped out of treatment? Those cases get buried in fine print. And don’t get me started on the 37% of CGMP violations for uninvestigated out-of-spec results. This isn’t healthcare-it’s a statistical illusion with pill-shaped consequences.

Savakrit Singh

December 7, 2025 AT 09:37Manufacturing in India? Of course. We have the best chemists, the cheapest labor, and the strictest quality control-wait, no, that’s not true. The FDA inspects us, yes, but how many plants get skipped because they’re "too busy"? The truth? We make the pills. You take the risks. 🤷♂️💊

Cecily Bogsprocket

December 8, 2025 AT 18:16I used to be terrified of generics after my cousin had a bad reaction. But then I learned how much care goes into every batch-the testing, the documentation, the cleanrooms, the 160-hour training for every worker. It’s not perfect, but it’s not careless either. This isn’t just about cost-it’s about dignity. Everyone deserves to be healthy without being poor.

Alex Hess

December 9, 2025 AT 09:11Wow. A 10,000-page ANDA? That’s not science-that’s bureaucratic performance art. If you need that much paperwork to prove a pill works, maybe we’re over-engineering the entire system. Why not just let the market decide? If it works, people buy it. If it doesn’t, they stop. Simpler. Cleaner. Less expensive.

Leo Adi

December 10, 2025 AT 09:49Back home, we call these pills "miracle tablets"-cheap, effective, and everywhere. No one cares if it’s blue or green. They care if it stops the fever. Maybe the real lesson here isn’t how they’re made-but how little we need to know to trust them.