Every time you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you’re holding the result of a long, complex journey that starts with a regulatory application and ends with a prescription being filled. It’s not just about copying a brand-name drug-it’s a precise, high-stakes process that ensures safety, affordability, and consistent access. If you’ve ever wondered why your $4 generic blood pressure pill looks different from the brand version but works the same way, here’s how it actually gets from a lab in New Jersey to the shelf in your local CVS.

The ANDA: The Gateway to Generic Market Entry

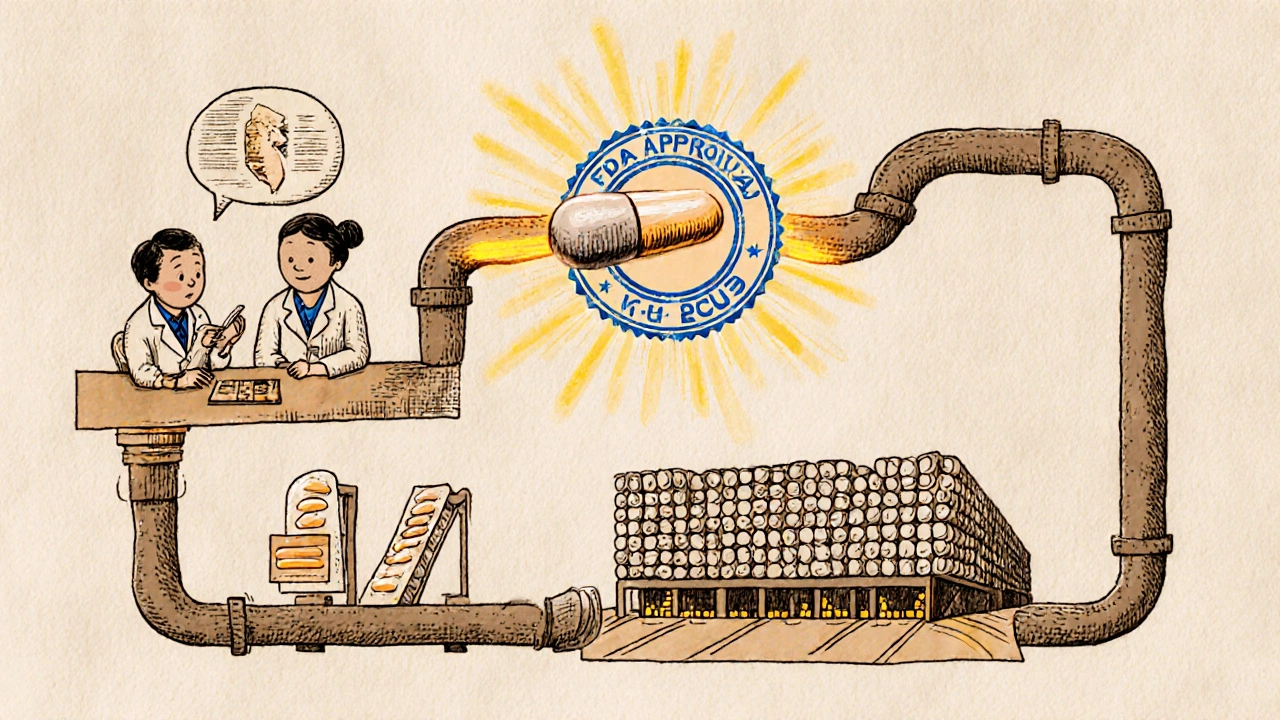

The Abbreviated New Drug Application, or ANDA, is the legal and scientific roadmap that lets generic manufacturers bring low-cost versions of brand-name drugs to market. Unlike the original drugmaker, who had to prove safety and effectiveness through years of clinical trials, generic companies don’t need to start from scratch. Instead, they rely on the FDA’s prior approval of the brand-name drug-called the Reference Listed Drug (RLD)-and focus on proving one key thing: bioequivalence.

Bioequivalence means the generic version delivers the same amount of active ingredient into your bloodstream at the same rate as the brand. This is tested in healthy volunteers using blood samples taken over time. If the levels match within strict FDA limits (usually 80-125% of the brand’s values), the generic is considered therapeutically equivalent. No need for new animal studies, no multi-phase human trials. Just solid chemistry, precise manufacturing, and proof it behaves like the original in your body.

The ANDA isn’t a simple form. It’s a 500+ page dossier packed with data on the drug’s chemical structure, manufacturing process, packaging, stability, and labeling. Everything must mirror the brand-down to the pill color and shape-unless there’s a valid reason for a change, like avoiding a trademarked design. The FDA reviews every detail. And it’s not easy: about 40% of initial ANDA submissions get rejected with a Complete Response Letter, often because of sloppy chemistry documentation or flawed bioequivalence study designs.

From Submission to Approval: The FDA Review Process

Once the ANDA is submitted electronically through the FDA’s Electronic Submissions Gateway, the clock starts. Under the Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA), the FDA has set performance goals. For a standard generic, the review takes about 30 months. But it’s not a one-size-fits-all timeline.

Some applications get priority. First generics-the first to file after a brand’s patent expires-get special attention. So do drugs in short supply, like antibiotics or insulin. The FDA’s 2023 report showed 112 first generics were approved that year, covering drugs worth $39 billion in annual sales. These are the products that can shift market dynamics overnight.

Patent challenges add another layer. If a generic company files a Paragraph IV certification-meaning they believe the brand’s patent is invalid or won’t be infringed-they trigger a legal clock. The brand company can sue, and if they do, the FDA can delay approval for up to 30 months. That’s why you’ll sometimes see multiple generic versions hit the market on the same day: six companies filed for the same drug, all racing to be first. The winner gets 180 days of exclusive marketing rights, a huge financial incentive.

Pre-ANDA meetings with the FDA are becoming more common, especially for complex drugs like inhalers or patches. Companies that use these meetings reduce major review issues by 30%. It’s not a shortcut-it’s a way to avoid costly mistakes before you even submit.

Approval Doesn’t Mean Availability

Getting FDA approval is only half the battle. Many generic manufacturers think they’re done when the green light comes in. But the real challenge starts now: getting the drug into pharmacies.

First comes manufacturing scale-up. A lab batch that produces 10,000 pills isn’t enough for nationwide demand. Scaling to millions requires revalidating equipment, training staff, and ensuring every batch meets the same strict quality standards. This phase alone can take 60 to 120 days. One company told Bioaccess LA that their first commercial run of a generic statin had to be discarded because the tablet hardness was slightly off-just 2% variation, but enough to fail FDA specs.

Next, the payer system kicks in. Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) like Express Scripts, OptumRx, and CVS Health control which drugs get covered and at what cost. They don’t care if the FDA approved it-they care about price, rebates, and formulary placement. A generic drug placed on Tier 1 (preferred) gets dispensed 75% of the time. On Tier 2, that drops to 35%. To get on Tier 1, manufacturers often have to offer discounts of 20-30% deeper than their original pricing model. One generic maker in Ohio said they lost $1.2 million in the first quarter because they didn’t negotiate a rebate with a major PBM fast enough.

Getting to the Pharmacy Shelf

Once the PBM signs off, the drug moves into distribution. Most generics go through one of the big three wholesalers: AmerisourceBergen, McKesson, or Cardinal Health. These companies have massive logistics networks, but adding a new product isn’t instant. Each pharmacy system must be updated with the new National Drug Code (NDC), pricing, and inventory codes. That process takes 15 to 30 days.

Then, the pharmacy itself gets the shipment. Pharmacists and technicians need to be trained on the new product, especially if it’s a complex formulation like a transdermal patch or a liquid suspension. Staff need to know how to counsel patients-because even though the drug is generic, patients often worry it’s not as good. A 2022 survey found that 40% of patients asked their pharmacist if the generic was “real medicine.”

On average, it takes 112 days from FDA approval to the first prescription being filled at a retail pharmacy. But it varies. Cardiovascular generics move faster-87 days on average-because they’re high-volume, low-complexity products. Inhalers and injectables? They can take 145 days or more. Why? More regulatory scrutiny, harder manufacturing, and fewer qualified suppliers.

Why This System Works-And Why It Matters

Over 90% of prescriptions filled in the U.S. are for generic drugs. In 2023, they saved consumers $313 billion. That’s not just a number-it’s a mother choosing between insulin and groceries. It’s a veteran paying $4 instead of $400 for his blood thinner. It’s a child getting antibiotics because the family can afford them.

The ANDA system was designed by Congress in 1984 to balance innovation and access. It lets brand companies recoup their R&D costs while giving patients affordable alternatives. Without it, drug prices would be unmanageable for most people.

But the system is under pressure. Generic prices have dropped 4.7% per year since 2015. Some manufacturers are leaving the market because margins are too thin. The FDA is responding by focusing more on complex generics-like nasal sprays and topical creams-that are harder to copy and still command higher prices. New rules, like the 2024 Data Standards for Drug Applications, will require more standardized electronic submissions, which could speed things up… but only if manufacturers can keep up.

Looking ahead, AI might help predict bioequivalence results or flag manufacturing flaws before they happen. That could cut development time by 25-30% in the next five years. But regulators are cautious. The FDA still wants human data, not just algorithms.

What This Means for You

If you’re a patient: trust your generic. It’s not a copy-it’s a legally required twin. The FDA doesn’t approve generics that aren’t as safe or effective. If you notice a change in how a generic makes you feel, talk to your pharmacist. It could be a different inactive ingredient, not the active one.

If you’re a pharmacist: educate your patients. Many think “generic = inferior.” Show them the FDA’s equivalence data. Explain the process. That builds trust.

If you’re in the industry: don’t underestimate the post-approval grind. Approval isn’t the finish line. It’s the starting gate. The real race is with PBMs, wholesalers, and pharmacy systems. Get those relationships right, or your drug never reaches the people who need it.

Are generic drugs as effective as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generic drugs to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name version. They must also prove bioequivalence-meaning they work the same way in the body. Over 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. are for generics, and studies consistently show they perform just as well in real-world use.

Why do generic pills look different from brand-name pills?

By law, generics can’t look identical to brand-name drugs because of trademark rules. So the color, shape, or markings may differ-but the active ingredient and how it works in your body are the same. These differences are only in inactive ingredients like dyes or fillers, which don’t affect the drug’s effectiveness.

How long does it take for a generic drug to reach the pharmacy after FDA approval?

On average, it takes about 112 days from FDA approval to the first prescription being filled at a retail pharmacy. This includes time to scale up manufacturing, negotiate with pharmacy benefit managers, integrate with wholesale distributors, and update pharmacy systems. Complex drugs like inhalers or patches can take longer-up to 145 days.

Why are some generic drugs harder to find than others?

Some generics are harder to find because they’re complex to manufacture-like transdermal patches, inhalers, or injectables. Fewer companies can make them, and the approval process is tougher. Also, if a drug isn’t profitable due to low prices or lack of PBM support, manufacturers may not bother producing it. Shortages often happen with older, low-cost drugs that have thin margins.

Can a generic drug be recalled after it’s approved?

Yes. Once a generic drug is on the market, the FDA continues to monitor it through inspections, adverse event reports, and lab testing. If a batch is found to be contaminated, improperly manufactured, or not bioequivalent, the FDA can issue a recall. In 2023, over 100 generic drug recalls were issued, mostly due to manufacturing issues or impurities-not because the drug didn’t work.

Ryan Airey

November 15, 2025 AT 16:49Let’s be real - this whole system is a rigged casino. The FDA pretends they’re protecting us, but they’re just letting Big Pharma and PBMs collude to keep prices low for generics so they can squeeze every last dime out of patients. And don’t get me started on how they approve a generic one day and recall it six months later because someone used the wrong dye. This isn’t science - it’s corporate theater.

Shyamal Spadoni

November 16, 2025 AT 06:12you know what’s funny? i read this whole thing and still don’t trust generics. i mean, how do you know they’re not just putting chalk in the pills? like, sure, the fda says it’s bioequivalent, but who checks the checkers? i’ve seen pills that look like they were made in a garage by a guy named bob who only speaks tamil and uses a coffee grinder to crush the active ingredient. and now they’re saying ai will predict bioequivalence? bro. if you can’t even get the pill color right without violating a trademark, how the hell are you gonna trust an algorithm? also, i think the fda is just a front for the cia. they need us to think we’re getting cheap meds so we don’t riot over healthcare. #trustthegeneric #butnotreally

Aidan McCord-Amasis

November 16, 2025 AT 10:3540% rejection rate on ANDAs? 😳 That’s wild. I thought generics were just copy-paste. Turns out it’s like trying to replicate a Michelin star dish with a toaster.

Katie Baker

November 18, 2025 AT 10:33My grandma takes 7 generics a day and swears by them. She says if they didn’t work, she’d be dead by now. Honestly? That’s all the proof I need. 💙

Hollis Hollywood

November 18, 2025 AT 18:33I’ve worked in pharmacy for 18 years, and I’ve seen patients cry because they can’t afford the brand. Then they get the generic, and they’re just… relieved. Not because it’s cheaper - though that helps - but because they don’t have to choose between medicine and groceries. That’s what this is really about. Not science. Not politics. Just people trying to stay alive. And this system? It works. Not perfectly. But well enough to save millions. I just wish more people understood that.

ASHISH TURAN

November 20, 2025 AT 09:15As someone from India, I’ve seen how generic drugs are made here - small factories, tight margins, sometimes questionable quality control. But I’ve also seen them save lives. The system isn’t perfect, but without generics, most of the world couldn’t even access basic meds. The real problem isn’t the generic - it’s the lack of global oversight. We need a WHO-style standard for low-income country manufacturers, not just FDA rules designed for US labs.

Chris Bryan

November 20, 2025 AT 17:58Let me get this straight - the FDA approves a drug made in a factory in Hyderabad, then ships it to CVS, and we’re supposed to believe it’s the same as the one made in New Jersey? That’s not science. That’s colonialism with a pill bottle. We used to make our own medicine. Now we’re importing it from countries that can’t even guarantee clean water. And you call this progress? 🇺🇸

Ogonna Igbo

November 20, 2025 AT 19:05you think this is bad wait till you see the real truth the american government is using the generic drug system to control the population through the pills you take the active ingredients are changed slightly over time so that you become dependent on higher doses and the fda is just covering it up they dont want you to know that your blood pressure pill is slowly turning you into a zombie but hey at least its cheap right

Jonathan Dobey

November 21, 2025 AT 09:16How quaint. We’ve turned the sacred act of healing into a spreadsheet. Bioequivalence percentages, Tier formularies, rebate negotiations - as if the human body is just another line item in a quarterly earnings call. The FDA doesn’t regulate medicine anymore - they regulate market share. And the real tragedy? We’ve convinced ourselves that ‘affordable’ is synonymous with ‘acceptable.’ We don’t want cures. We want cost-efficiency wrapped in a white pill and labeled ‘FDA Approved.’ How poetic. How tragic. How… American.

John Foster

November 22, 2025 AT 04:00There’s a silence in this system that no one dares to name. The pills don’t talk. The regulators don’t explain. The manufacturers don’t apologize. And the patients? They just swallow. And swallow. And swallow. We’ve turned pharmaceuticals into a ritual - a silent communion between corporate algorithms and human desperation. No one asks why. No one dares to question. We just take the pill. And hope. And wait. And hope again. Is this medicine? Or is this just another form of mass hypnosis dressed in blue and white capsules?

Edward Ward

November 24, 2025 AT 02:12What’s fascinating - and terrifying - is how much of this process is invisible to the end user. We think we’re just picking up a $4 pill, but behind it is a global chain of patents, lawsuits, manufacturing recalibrations, PBM negotiations, warehouse logistics, pharmacy software updates, and pharmacist training sessions. It’s a symphony of bureaucracy, and yet we treat it like a vending machine. The real miracle isn’t that generics work - it’s that they ever reach us at all. And we take it for granted. We should be grateful. We should be outraged. We should be doing something. But instead? We just take the pill.

Jessica Chambers

November 24, 2025 AT 15:12So… we spent 112 days getting a pill to the shelf… and you’re all acting like it’s a miracle? 😒 Meanwhile, in Germany, they do it in 45 days and don’t need 500-page dossiers. But sure, let’s keep pretending this is the pinnacle of medical innovation. 🙄

Adam Dille

November 25, 2025 AT 12:58Really appreciate this breakdown. I used to think generics were just ‘cheap versions’ - now I get how insane the process is. Also, 40% rejection rate? That’s wild. I feel bad for the chemists who spent a year on a submission just to get a ‘complete response letter.’ 😅

Andrew Eppich

November 26, 2025 AT 15:21The notion that generic drugs are equivalent to brand-name drugs is a convenient myth perpetuated by regulatory capture and pharmaceutical lobbying. The FDA’s bioequivalence standards are insufficient to guarantee therapeutic parity. Clinical outcomes are not measured. Patient variability is ignored. The system is designed for cost containment, not clinical excellence. One must ask: if the difference is truly negligible, why does the original manufacturer spend billions on R&D while the generic producer spends nothing? The answer lies not in science - but in economics.